Introduction

Frequent visitors to my blog will know that essentially I have one other post about how hard and slow it was making a small website in a federal department. Over the summer, I was complaining about describing the compliance process to my sister and she was like, “Yeah Paul, it’s the government. If you don’t like paperwork, why do you work there?”

Wow, Julia, go for the jugular, why don’t you?

I’ve been a civil servant my whole working life — in Canada, in the UK, at Western U’s ‘student government’ — and I’ve always had interesting stuff to work on and great colleagues. In fact, the public servants I know regularly go above and beyond — often overcoming awful processes and dated technology to get things done.

But let’s not get the wrong end of the stick here: it’s obvious to anyone with any sustained interaction with the Canadian government that our public service isn’t out here winning Design of the Year or automatically filing our taxes (yet). More often we see stories about big, expensive IT failures and generalized anxiety about “old mainframes and technology, some on the verge of collapse.”

My sister’s perspective that ‘government is just inherently slow and paperwork-heavy’ isn’t what you would call deeply nuanced, but there’s definitely a link between her pessimism and a pattern of costly failures. So how do we square this circle: how is it that so many dedicated and well-meaning public servants working all over the government deliver so much crappy software?

When we start seeing patterns like this — similar outcomes from disparate departments — it’s a pretty sure sign that we are dealing with systems rather than particular teams or individuals. A strong swimmer traveling against the current will always go slower and use more energy than an average swimmer (like me) swimming with the current. When a system works against you, you spend more energy and get less done — eventually wearing down even the most talented folks.

So let’s talk about systems: what they are, what they do, and how, sometimes, the problem isn’t when our systems stop working, it’s when they work too well.

Systems: a working definition

A system is a set of parts working together. Broadly speaking, systems are created when you need to do something more than once. Systems can be composed of physical parts (like a car), but for this post I will focus on systems as sequences of actions. For example, Basically Spaghetti Pomodoro is a sequence of actions resulting in, arguably, “THE best pomodoro sauce I’ve tasted at home.”

Good systems know what ‘good’ looks like and have the flexibility needed to improve over time. In the UK, anyone can apply for a new passport entirely online by submitting a digital photo from their smartphone. In Canada, you need to bring in a physical regulation-sized photograph with a stamp and a ‘wet-ink’ signature on the back. Obviously, whoever designed the passport system several decades ago didn’t anticipate ubiquitous digital photography, but a good system adapts to a changing context.

If good systems have clear priorities and are adaptable, bad systems are inflexible and confused about what is important. Even systems created with the best intentions degrade over time, so being able to cope with new situations is crucial.

What does this have to do with government?

Systems have everything to do with government. I’ve defined a system as a set of parts working together to achieve a goal — in a broad sense, a government is the same thing. More narrowly, governments love a good recipe. Whether you call them ‘policies,’ ‘processes,’ ‘procedures,’ or ‘paperwork,’ (or any other thesaurus.com alternative), government is stuffed with systematized ways of completing tasks.

Sometimes these heavily-routinized approaches get out of hand, like when releasing a small website means writing a novel’s worth of paperwork. Governments are notorious for this kind of over-the-top bureaucratic process (known as ‘red-tape’).

While writing 36 thousand words is obviously too much for a simple website, this isn’t a post to make that argument. Instead, I want to talk about why is it like this? How did we end up with processes that are okay with writing 36 thousand words?

Systems don’t always work that well, but they are always supposed to. The processes we encounter — even if they seem illogical — were all deliberately introduced and there’s a reason they are still around. Usually there is an important principle they are meant to upload, it’s just a matter of finding it.

In the world of traditional government IT, there is one fundamental principle that almost no amount of usable software is worth trading for, and that principle is “enterprise.” Investigating what it means to be ‘enterprise’ (and build ‘enterprise software’) helps us to better understand the processes we have, the teams created to enforce those processes, and how, ultimately, we get the outcomes we deserve.

The Enterprise approach

The Canadian federal government, to a degree I never experienced in the UK, loves the word “enterprise”. ‘Enterprise’ is used both as a descriptor and an aspiration: it describes the kind of organization we are, but it is also an all-important principle to uphold.

Before joining the Canadian public service, my understanding of “enterprise software” was something closer to ‘an ugly and hard-to-use backend system imposed on a captive workforce,’ but obviously this was just an uninformed impression and has no bearing on reality. Anyway, we’re here now, so let’s give it a fair shake.

The fundamental idea behind ‘enterprise’ is ‘consistency.’ If you are an ‘enterprise,’ it means you are a large organization with lots of teams and you want to make sure you are doing the same thing across those teams. Broadly understood, we could sum up the ‘enterprise’ mindset as: “if we have the same problem in different places, we should solve it the same way.”

This idea(l) is essentially positive and it appeals to an innate sense of fairness and objectivity most of us would agree with: that governments shouldn’t discriminate between people. For example, if I apply for a passport from Rivière-du-Loup, it wouldn’t be fair for it to cost twice as much it would in Ottawa.

Much of the time, this focus on standards is useful. There are lots of things it makes sense to standardize on: team calendars, predictable email addresses, headers and footers that don’t change as you move between different sections of a larger site. The consistent look-and-feel shared by (most) departmental websites is a triumph of enterprise-centric thinking.

Moveover, it’s also risky for government services to be inconsistent. Governments can be sued for failing to providing consistent outcomes — for example, when government services aren’t accessible to different types of users. Thus, consistency can help both to simplify internal workflows and protect government departments from potential lawsuits.

But like with any high-minded principle, you can take ‘consistency’ too far — say writing a book’s worth of oversight documentation for a small site because it’s what you would do for a large site. While this level of oversight can seem absurd, it begins to make sense if we assume a core organizational principle of ‘consistency at any cost’ (sometimes literally, considering IT budgets for large projects ).

But processes and principles are just words; organizations are made up of people. The outputs of any system depend on the people working within it, and we can learn a lot by looking at the makeup and incentives of internal teams. Specifically, enterprise-first environments tend to create silos of specialists that focus on internal oversight rather than external outcomes.

Single-disciplinary teams

Enterprise environments love creating single-disciplinary teams: teams in which everyone has the same skill set (eg, a legal team of lawyers). Single-disciplinary teams are rooted in a desire to ensure consistency across a line of products. These teams are responsible for creating org-wide standards, and for advising and approving products (but rarely for building them).

On first blush, grouping people by role and giving them oversight across a range of products might not seem like too bad of an idea, but pretty quickly you start losing time and context as projects bounce around between these narrowly-focused teams. However, these are emergent problems: they aren’t obvious at the outset but get worse as organizations grow. Let’s see how some of these dynamics play out by running through an imagined scenario.

The toll road to enterprise: a thought experiment

Let’s imagine we run a small company. Let’s call ourselves EasyTax: we make a tax filing app for Canadians, and we have 6 employees in total: two developers, a designer, a marketer, a tax lawyer, and a founder who is responsible for product decisions. At this point, we have 1 product and 1 team. Each member contributes their specific expertise while also understanding the overall goal: building a great tax filing product.

A few years later, our tax software is so popular that we have 5 different apps for different tax-filing scenarios: for individuals, for businesses, for students, for pet-owners, for government tech bloggers. Now there are 5 product teams, one for each app, and all with the same makeup as my original team.

On our 5 individual teams, we have 5 individual designers. But since each team works independently, variations emerge between products. When filing taxes, there are a large list of credits to sort through.

- One team keeps them all in a big list

- Another team uses accordions to show or hide tax credits

- A third team has a search box to look them up

Even though ‘showing tax credits’ is a common experience between all of my products, my designers are working independently and have implemented different solutions.

Under the ‘enterprise’ model, this is no good. We don’t want each designer coming up with stuff on their own — now we have inconsistent outcomes. To rectify this, let’s create a centralized team made up only of designers. This new team will create ‘best-practice’ designs (eg, for showing tax credits) and then standardize it across products. This means individual product teams no longer have a dedicated designer, but instead we have a ‘design team’ responsible for reviewing and approving designs for every team.

If we imagine each of our products as a pie, we started with 5 pies and each pie had 1 designer assigned to it. Now, we have 1 consolidated design team responsible for a 10% slice of every pie — but only for how the pie looks, it doesn’t matter how it tastes.

Now that the design problem is solved, we want to do this with other roles too. Let’s create a legal team, a marketing team, and an architecture team. Instead of working on specific products from start to finish, each of these specialized teams is responsible for a slice of all products, so now all of our pies look like pie graphs (see figures below).

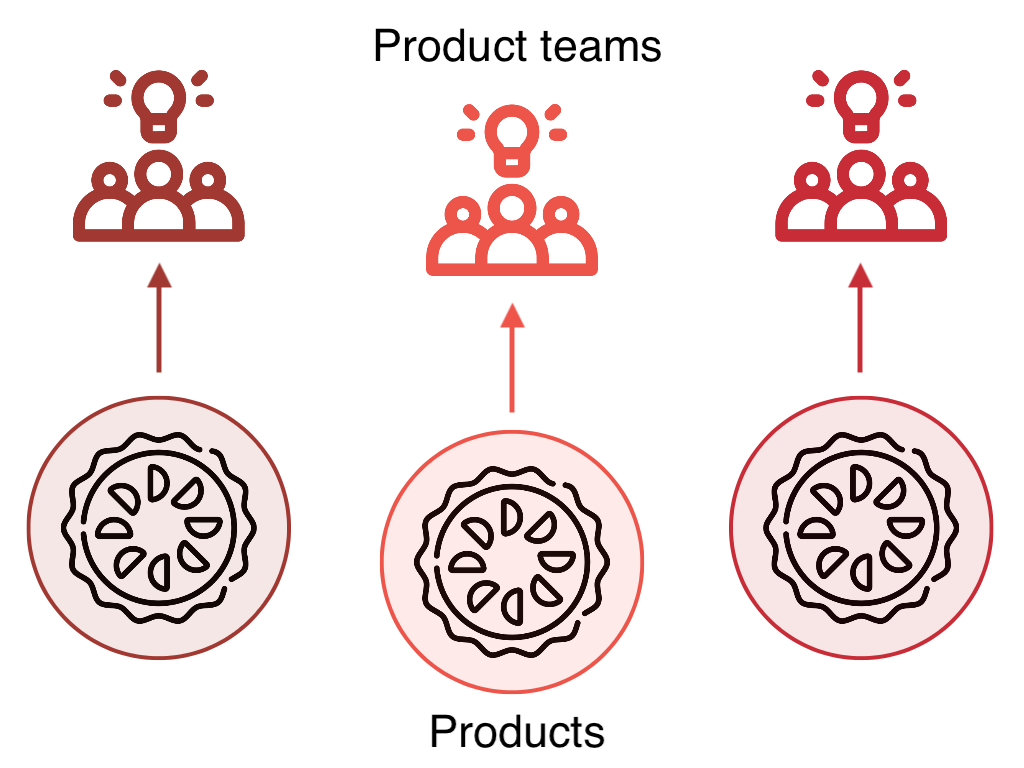

Figure 1: Product teams with clear responsibility

3 autonomous product teams, each responsible for 1 product. Arrows represent responsibility for products. Responsibility is clear: there are 3 arrows, each product team is responsible for 1 product.

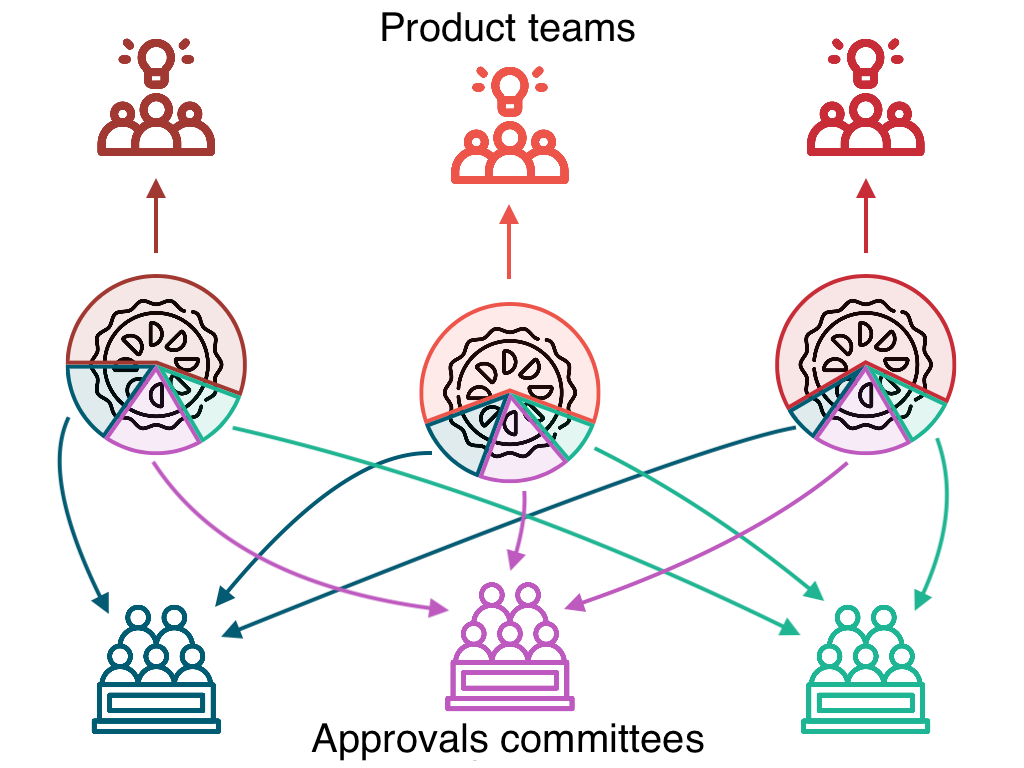

Figure 2: Advisory teams with complex responsibilities

3 product teams and 3 advisory teams, sharing responsibility for 3 products. Arrows represent responsibility for products. Responsibility is complex: there are 12 arrows, each product team is mostly responsible for 1 product, and each advisory team is partially responsible for every product.

Each time we create a new centralized oversight team, the actual team doing the work gets smaller, while the number of people “involved in oversight, gate-keeping, and green-lighting” increases. The upshot of this process is that we are losing more time in meetings while reducing overall team capacity.

With all of our oversight teams ‘advising’ on every product, things start getting pretty confusing. (Imagine organizing an enterprise-style potluck where each person invited needs to provide 1 ingredient for every dish.) A lot of time is lost emailing to coordinate reviews and approvals for all our ongoing work. To address this, let’s come up with a really clear and detailed plan that outlines exactly what everyone needs to do at every step.

Here is an example of what our really detailed and not-confusing plan might look like. (psst, read the notes for the slide.) It’s a little hard to see in the diagram, but it visualizes an internal release pipeline that includes 93 discrete steps.

So, in this thought experiment, what started as a fairly intuitive team structure where everyone works together on a shared goal has turned into a highly choreographed performance where products ping-pong around between teams that mostly watch, rather than do.

In breaking up our product teams into siloed teams of specialists, we do have clearer standards in place although now everything takes longer. But is this actually a problem? Things are slower with all the extra meetings, but isn’t this preferable to an organization of uncoordinated, independent teams potentially overlooking the bigger picture?

Well, it turns out there is more than just one bigger picture. There is a short-term and a long-term cost to this kind of org structure. In the short term, teams narrowly-focused on a single domain can end up missing the forest for the wrong forest. And in the long term, an over-emphasis on following standards can easily lead to internal stagnation.

Short term: oversight that misses the point

Once upon a time, I was on a team building a user recruitment site. After putting together some early designs and beginning work on the first few pages, we reached out to the oversight teams we needed approval from.

The group advising on data security looked over our designs and frowned at the signup form. They strongly advised us to remove the ‘email’ field. If we did that, they said, it would be easier to approve our project because not collecting personal data is better for data security.

But the whole point of our site was to collect the emails of interested users, we rebutted. How would we follow up with people if we had no way to contact them?

‘Well, I am just telling you, it will be harder to get it approved this way,’ was the response.

Well-meaning advice, to be sure, but it completely overlooked our team’s goal. It didn’t make sense to build a user recruitment website that couldn’t actually recruit users. From our perspective, this group didn’t understand the bigger picture of what our site was for.

However, from the data team’s perspective, we were the ones missing the big picture. Their responsibility was data security writ large, and data you don’t collect can never be hacked or leaked. Their standard recommendation — ‘don’t collect emails’ — was consistent with their goal of reducing personal data collection across the organization. So there was actually a bigger picture here, it was just the wrong bigger picture for our site.

“A foolish consistency is the hobgoblin of little websites”

— Ralph Waldo Emerson, replying-all after our meeting

Despite the surrealism of that discussion, we ultimately kept the email field and went on to launch the site. Even though we spent some time in unproductive meetings, we still got our way in the end. Problem solved, right? Well, maybe in the short-term, but in the long-tem, this ‘enterprise’ preference for rigid standards over flexible implementation can result in a stagnant organizational culture incapable of incorporating new tools or ideas.

Long term: oversight as bureaucratic cement

In an enterprise organization, local variations are heavily discouraged. They aren’t impossible, but they’re certainly not easy. Under normal circumstances, you shouldn’t do things like:

- install applications that aren’t pre-approved

- add new technology to your tech stack that hasn’t been vetted

- use designs that aren’t standard

- sign up for new services other teams aren’t using

In my previous article, I outlined how a ‘maximum risk’ interpretation of adding a CMS to our website resulted in excessive documentation. On this same team, we burned a lot of time and energy requesting an online task-tracking app (a bit like a team todo-list: you use it to keep track of who is working on what). The reason it became such a sticking point was that a different task-tracking app was internally pre-approved for all teams to use.

To take the ‘enterprise’ perspective: there was already a standard solution in place and our team was being troublesome in trying to contravene it. If this application really was that much better, why didn’t we use the “request new software” process and submit it as the new standard for all teams to use? Why should we be different, picking our own thing that nobody else was using? Moreover, everyone knows it’s cheaper to ‘buy in bulk’ rather than spending small amounts for one team at a time.

It took us about 6 months of intermittent meetings, written justifications, trial accounts, etc, before it was finally approved for our use. ‘Buying in bulk’ to save money is a good theory, but it doesn’t consider the loss of productivity from teams finding workarounds for clunky tools — not to mention the cost of these long-running discussions. We likely spent more money in employee salaries to attend meetings and write documentation than if we had been allowed to make a low-cost purchase on a credit card.

In my past job at the UK government, we would have made our decision in the morning and had it set up by the afternoon.

In the short/medium term, problems like these can often be resolved. However, the pernicious long-term effect is one where it costs so much time and energy to introduce new ideas or processes that eventually your whole tech stack (and maybe your homepage) looks like it came out of a time capsule. The ‘enterprise’ preference for layering on oversight and approvals is essentially a kind of bureaucratic cement that slows down your organizational agility over time.

Without an easy way for teams to try out new technologies, new software, and new designs, you wind up stifling your long-term ability to incrementally modernize. It’s true that consistency is important, but, taken to an extreme, it can lead to a situation where teams are structurally unable to introduce new ideas. Once that happens, you end up relying on massively expensive, hugely disruptive ‘transformation/modernization’ megaprojects, which try to introduce a raft of new technologies and process changes all at once. In other words, exactly the kind of large IT projects that fail most often.

An enterprise exit plan

Hopefully by this point you’re open to the idea that ‘enterprise’ is Not That Chill. Consistent look and feel and standardized outcomes are important principles, but not when it means multiplying all your timelines by a factor of 10 and losing internal cohesion to information silos.

However, as Billy McFarland famously said “We’re not a problems-focused group, we’re a solutions-oriented group, we need to have a positive attitude about this.” It’s all well and good to burn down 50 years’ worth of organizational theory in a blog post, but what are my solutions?

It’s a fairly long post already, so I will be (relatively) brief — but I plan to expand on these themes in future posts (sign up! It will be a hoot! ).

This post has focused on two problematic aspects of ‘enterprise’ culture:

- ‘Consistency’ as the all-important principle to uphold

- Single-disciplinary teams that approve products but don‘t build them

Let’s address them in reverse order.

Better teams: Multidisciplinary instead of single-disciplinary

‘Enterprise’ organizations rely on single-disciplinary teams where everyone has one skill but works across many products. If we compare this way of working to how teams are organized in modern software companies (or modern teams in other governments) we see exactly the opposite approach being implemented successfully. Multi-disciplinary teams work on one product and include all the skills needed to build and operate a working service.

Importantly, these teams must have authority over their products. Multidisciplinary teams working in an oversight-centric ‘enterprise’ environment are able to design and build their own products to some degree, but team decisions can always be vetoed by groups with approval authority. Creating multidisciplinary teams is a good start, but their effectiveness will be limited if they can still be overruled later.

If we rewind to the start of our EasyTax thought experiment, this is exactly the kind of team we started with. Small, multidisciplinary product teams chat with each other instead of booking meetings, and all team members understand the overall goal they are trying to achieve. By keeping teams nimble and reducing organizational gatekeeping, we end up with teams that are more effective: taking less time to deliver services that users prefer.

A better principle: User needs over consistency

In an enterprise organization, ‘consistency’ isn’t just a ‘nice-to-have’, it’s the central assumption from which everything flows. The standards-centric mindset of the enterprise approach is a really clear principle: it helps us structure teams, put together policies, and suggests how to approach decisions. To quote Archimedes, “Give me but one firm spot on which to stand and I will move the earth.” If we scrap ‘consistency,’ where do we stand?

The answer is ‘user needs’. User needs is the #1 design principle in the UK government, and incidentally, it’s also at the top of the Government of Canada’s Digital Playbook. Whenever you find yourself at a crossroads, ask ‘What is best from a user’s perspective?’

Let’s think about applying for a passport in Canada: would it be better to allow digital uploads or to stick with physical photos? Taking a departmental perspective, physical photos are harder to fabricate and we currently have the resources and expertise to manage them. But let’s reframe this from the end user’s perspective: What will make this service the easiest to use for the most people? If we asked 10 people at the mall right now, what would they tell us? Undoubtedly, we will find that digital uploads are preferred by people applying for passports in Canada today.

The example of the user recruitment site I worked on is revealing here too. You can understand why the data security team would suggest removing the email field from the signup form, but no user would ask for that change.

‘User needs’ corrects for a serious bias in our org design. Of all the internal teams we have to meet with to triple-check and approve all of our decisions, the actual users of the service are almost never present in these negotiations. You can get approved by every group you have to meet with, and still end up releasing a site that doesn’t work for its intended audience. This is how you end up with problematic launches like the original healthcare.gov, where, despite the huge number of people involved (and an eye watering amount of cash), it failed as soon as real people tried using it.

Better systems for better systemic outcomes

Keeping an eye on the big picture is important, but we have multiple bigger pictures to choose from. The best bigger picture is the one that puts end users first — it’s the most likely to lead to services that are clear and easy to use. Under an ‘enterprise-first’ organization, many of the procedures set up are internally-focused, with compliance teams asking themselves ‘What is best for this department?’ We need to transition to processes that look outwards, asking what is best for Canadians.

The systems we encounter at work are not inevitable or eternal. They are designed and implemented by human beings, and when they work properly, they help us get things done more easily than if we didn’t have them. Good systems are useful, adaptable, and consistently deliver good outcomes. Once a system is none of these things, it’s time to change.