Introduction

As a cool Paul who blogs, like Paul Wells or Paul Graham, not only do I derive tremendous advantage and prestige from my posts every 3 months or so, but I also get to write fun and interesting articles heavy on structural critiques and relatively light on clear solutions. Catching on to this, sometimes folks reach out to say something like: ‘it’s a good analysis of the problem, but “just do agile” isn’t actually a specific-enough solution for me’.

Traditionally my answer has been (and remains), ‘multi-disciplinary teams with delegated authority.’ As in, teams with all the skills they need to solve the problem building the best solution they can in an iterative way (without needing approval for everything 2 years before). Which sounds good in theory, but I’m sure plenty of folks in various governments have seen agile teams tried without much success. And I totally get it: often you see innovation-y projects that assemble a handful of folks from different parts of the org who then start doing sprints. And that’s a pretty good start (really!), but in my experience there are a couple pieces of the puzzle notably missing if that’s all you do. Teams like this can easily run into unanticipated problems related to facilitation and overall product vision. So, somewhat uncharacteristically, I actually have two really clean recommendations for you in today’s article.

When I moved between the UK government to a Canadian federal department, one of the largest differences I noticed was in how agile teams were put together. My department in the UK primarily hired people from outside government, already familiar with ‘new ways of working,’ while my Canadian department was mostly moving existing staff into new roles. And that’s great! You’re never too late in your career to learn something new, and many of the folks I met were excited to work in a new way that would ultimately improve outcomes for citizens. But at the end of the day, ‘digital transformation’ is about introducing new tools, new ways of working, new responsibilities, new lots of things. Transforming successfully means you will need to bring in a bit of ‘new’ as well.

In Canada, I’ve run into two major roadblocks to introducing successful agile delivery:

- Firstly, despite an obsession with documentation, somehow we rarely see an easily-understood representation of the thing we’re trying to build.

- Secondly, the traditional approvals-based approach audits specific aspects of new products, but doesn’t have much to say about holistic product ownership.

Luckily for us, these two problems map onto two new roles:

- Someone responsible for leading the process of arriving at then producing product designs.

- Someone responsible for product strategy, prioritizing feature development, and ensuring business and user needs are being met.

Or, to speak plainly: hire a Designer, and hire a Product Manager.

How does it work now?

In the following section, I’ll take you on a whirlwind tour of some of the internal artefacts created in the waterfall product planning cycle, based on my recent experience in one of Canada’s largest federal departments.

In a waterfall system, specific roles have an org-wide accountability for a specific pie slice of every product — usually they create standardized artefacts used for internal approval. But these groups are narrowly-scoped so by definition they don’t have the full picture, and they aren’t trying to create one either. It’s a bit like if you tried to solve a 100-piece puzzle by giving 10 pieces each to 10 different people.

But I digress, we have a product to build and only 4 years to get it out the door.

1. The business case

Let’s say we’re building a product to provide answers to people who are flooding our call centers: since FAQs are passé now, let’s call it a “Knowledge Base” (KB). Basically, we want to build a product where people can publicly post questions and get written answers from staff (or a chatbot). The next time someone looks up that same question, Google will hopefully send them to the official answer on our Knowledge Base and they won’t need to phone us. So far, so good.

Now that we have agreed on the solution that we want, we are going to write a business case about it (sorry “start with the problem” folks, but that’s not how you get funding — the ‘funding’ phase comes after your detailed business case). The group writing the business case is a ‘program team’, responsible for initiating and managing internal ‘programs’ — usually, programs focus on building or improving services.

A business case does two things: it describes the outcome we want and estimates what it will take to build it (cost, resources, timelines, etc). A business case justifies taking on a given project: by spending x amount of money, we can build this new system to help our users get answers faster, which will save us money in the long term rather than continuing to pay our call center staff overtime.

This is what the service being described looks like as a business case:

Figure 1: Sample business case

Two pages of a word document, representing a sample business case.

What we get is a large Word doc (comparable to a novella) with rationales, budgets, timeframes, and expected outcomes. Neat! Anyone reading through it should understand the intent and the goals of our new product and get an upfront cost estimate, but there are still a lot of details to be filled in here. For example, what am I going to see when I am on the homepage? How do people interact with the chatbot?

So it’s good that we’re on the same (56) page(s), but the potential for misalignment starts at the beginning. Without something more tangible, important gaps in understanding may not be surfaced until much later. If you created a written description of a lamp and then asked 3 people to go into separate rooms and sketch you a lamp, you are going to end up with 3 different lamp designs.

Okay, so it’s a start, but clearly we still have some work to do. Let’s move onto one of our early technical deliverables: an application architecture diagram.

2. The architecture diagram

Since we’re talking about a big IT system, we are going to need a big IT diagram. At this stage, we look at our current IT infrastructure and see how this new application fits into it. What existing applications do we have, where can our data come from, and where should it end up? What is new, what can we reuse? Answering these questions means modifying our existing diagram so that it also includes our new Knowledge Base.

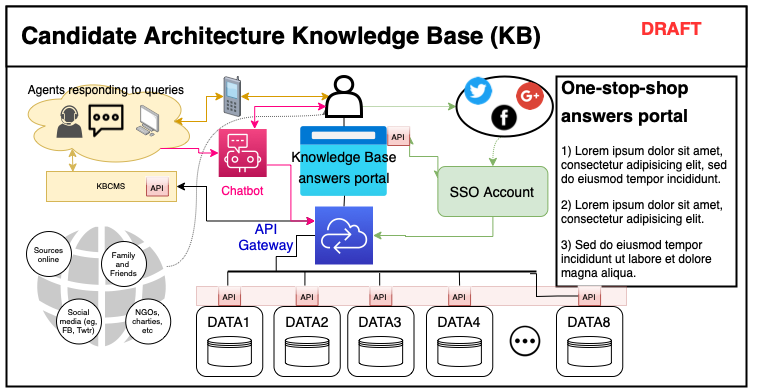

Maybe this means adding several new boxes, or maybe only one. Or maybe some of our existing boxes need to be modified and a one or two new arrows added. By the end, we end up with a PDF that might look something like this:

Figure 2: Sample architecture diagram

A sample architecture digram, depecting how our hypothetical new product connects to our also hypothetical IT infrastructure.

For modelling a system, it’s great that we have an architecture diagram — a little forethought goes a long way. Of course you want to think this through before jumping into a big new project. But, for the layperson, this is practically indecipherable. Like our business case, there is no way to look at this representation and imagine how it will actually work in practice. Again, what will the homepage look like?

But maybe this is to be expected: after all, this is a specialized document meant for a specialized group — most people can’t read sheet music either. This isn’t really intended for general consumption, but as a guide to orient our technical decisions and as a reference point when we are considering down-the-road implementations.

So let’s keep our fingers crossed for the next one: this is the stage when we want general-purpose artefacts to shop around to our stakeholders and get feedback on what we’re building. And (in a marked difference from my time in the UK) almost all of this internal communication between different groups happens via slide decks.

3: The slide deck(s)

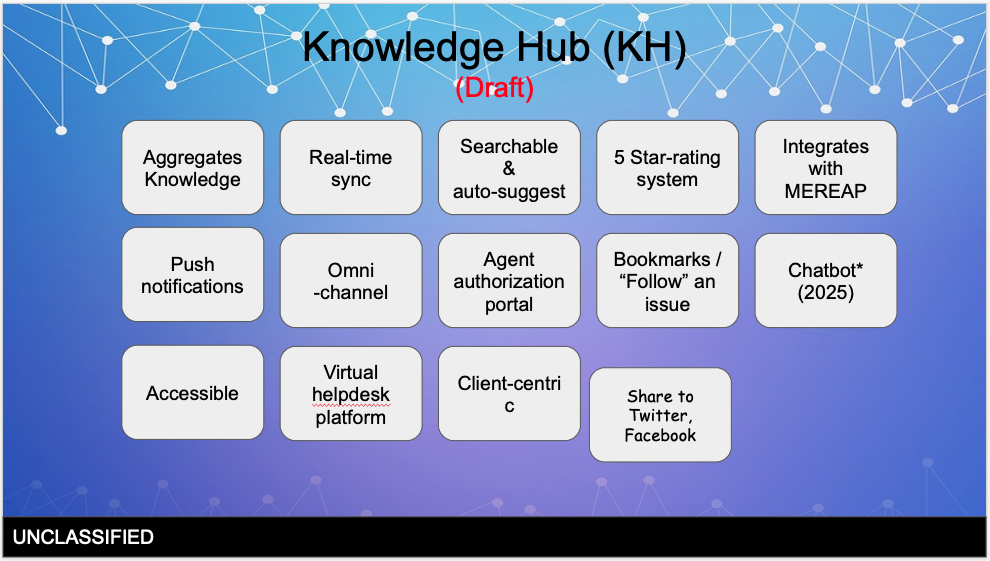

At this point we know we are building a product, we have described the outcomes we are trying to achieve, and we have a technical diagram. But we still don’t have an easy way to describe what this new product is to people who are just hearing about it for the first time. And maybe this is the point where it would help to have an easily understood, semi-realistic representation of our new product that we can quickly show people. Or… maybe we whip up something like this:

Figure 3: Sample slide from our Knowledge Base slide deck

A sample slide from a hypothetical PowerPoint deck introducing our Knowledge Base.

At this point, we are trying to get across the main idea, but since no one on the team knows Photoshop, we are doing our best with PowerPoint. Just because we don’t have a knack for building interface mockups, doesn’t mean we can’t give it the old college try, eh? As anyone who’s been in government for a few years knows, there is no limit to the fun and creative formatting options available in PowerPoint. We could play it safe with dependable bullet lists and tables, or maybe we add a bit more pizazz with a little clipart car driving along a road that passes all our milestones (metaphor!).

As we meet with different groups to introduce our upcoming Knowledge Base, we will get suggestions for new features, which we can add in as new boxes on our slide. Sometimes we get genuinely good recommendations, but there are a couple of other (bad) reasons why suggested new features are incorporated at this point:

- Some of the groups we are meeting will be the ones we need approval from later. If they suggest something, we are more likely to get our product approved if it’s included.

- In waterfall product development, the “planning phase”, in which all the planning happens, is followed by an “implementation phase” in which all of the implementation happens. Anything not included during the planning phase is difficult to add later, so our incentive is to take the ‘kitchen sink’ approach where we squeeze in as many ideas as we can upfront because later it will be too late.

After doing the rounds internally and making requested updates, we are ready now to start implementing — whether using an internal IT team or a contracted vendor team — and given the 3 artefacts we’ve created so far, we are going to cross our fingers that it’s clear enough to be handed off at this point.

What’s going wrong here?

At this point, let’s pause our somewhat (but not wholly!) contrived product development process and talk about what’s missing. The two roadblocks I described earlier were:

- What is the thing? We haven’t yet created a product visualization that helps someone easily grasp the product. This means it’s hard for our colleagues (or end users) to give us useful feedback.

- What is important about the thing? Our business case describes desired outcomes but our slide deck just contains a laundry list of desired features. Are they all equally useful? Are there any that we don’t need right away? Or that we don’t need at all?

1. What is the thing?

At each stage, we have created an abstract representation of the system that is needed for a specific milestone, but none of them give us a quick and easy way of visualizing what we are looking to build or explain why this is the best thing to build. Each approvals group is only interested in one aspect of the product, so we are continually creating partial representations. To be clear, it’s not that we don’t need, say, an architecture diagram, but the problem is that “getting a clear, easily-understood depiction” is nobody’s responsibility. None of these documents are much help to someone just hearing about this project for the first time.

Enterprise product development means lots of meetings with lots of different groups and something that would be really helpful in this environment is a clear, easily-understood depiction of the thing you’re trying to build. It’s easy to say, for example, “we are trying to build a product that answers the most common questions we get at the call centre”, but that’s still not enough to go off of if we want to have informed discussions and gather meaningful feedback. And if that’s all you have when you contract an IT team to build your product, well, it’s anyone’s guess what you’re going to end up with by the end.

It’s a bit like those medieval lion sculptures you occasionally see that don’t really look a whole lot like lions.

Figure 4: A medieval sculpture of a lion

A medieval lion with human eyes and teeth, and a big moustache.

Maybe a medieval project manager handed over a list of lion requirements (teeth, facial hair, 2 eyes) to a sculptor who had never seen one before. In the end, we get something lion-adjacent but there’s something pretty weird about its teeth and moustache. You can imagine it might have turned out better if you could have shown the sculptor a picture of a lion first instead of a 56-parchment requirements document.

2. What is important about the thing?

Perhaps more fundamentally, none of the documents we have created thus far really focus on validating the problem we are trying to solve. Approvals groups have narrow slices of responsibility, which means you can end up meeting all the requirements you get from various teams and releasing a product with a clunky user experience (eg, Healthcare.gov launched with ~8-second load times between pages).

Let’s use a hypothetical example to illustrate this: imagine we had a security requirement recommending we log people out frequently to protect their data. We don’t want someone logging in at a library and then the person after them gaining control of their account. Of course there are other aspects to consider — design, accessibility, architecture, etc — but the security team knows that that expertise lives elsewhere in the org. So the product team asks ‘how long can they be logged in?’, and the security team says ‘the shorter the time frame, the better for security.’ Someone suggests 15 mins before logging people out and the security team says ‘That works for us, you are approved.’ Now the team has a clear direction and approval to move forward — win-win. The only group to lose out is anyone using this service in the future, because getting logged out every 15 minutes would be awful.

To clarify, a 15-minute logout limit is a made-up example to underline a point, not something that I’ve ever come across. But what’s true here is that by moving responsibility away from the team and into so many oversight groups, you end up with fragmented product ownership and requirements that don’t always consider the holistic experience of your eventual users.

And it’s hard to blame the team here: it’s completely rational for teams with overlapping sets of requirements to pursue the path of least resistance for getting approval, even if it results in a product that is hard to understand and logs people out too often.

Won’t somebody think of the users?

So far, I’ve focused on internal dynamics of waterfall product development because they take up so much time and energy. But let’s keep in mind what isn’t being prioritized here: talking to the real people who will end up using whatever it is we build.

As a product evolves from an outline in a business case to a more definite list of requirements, all kinds of specific detail is added: whether there will be user accounts, how long before you are logged out, if it makes sense to include a chatbot, etc. Usually, these requirements are essentially just hunches, and the more of them you add up, the less chance you have they will all be right. It cannot be emphasized enough, it’s a much better idea to spend a few thousand dollars and a few weeks seeing if people like your chatbot idea than spending millions of dollars building the real thing over 3-5 years before anyone ever even sees it.

But here’s where our two problems create obstacles towards reaching out to users. First of all, we don’t have an easily-grasped prototype or mockup, which means it will be really hard to get meaningful feedback. And secondly, we don’t have a clear role on the team responsible for connecting the feedback we do get to an overall product vision.

Agile to the rescue?

Loyal readers will know that at some point I am always like ‘my ally is Agile and a powerful ally it is. ’ And I’ll get there, don’t worry. But, given all we’ve discussed so far, just being ‘more agile’ right now isn’t likely to help.

One of the key agile recommendations is changing from single-discipline teams giving approvals, to multidisciplinary teams staffed with all the skills needed to design and build products. Theoretically, this is pretty straightforward, you use your Roller Coaster Tycoon tweezers, grab one person from each discipline in your department, and drop them all in the same boardroom until they ship you something that looks like AirBnb. The idea is to create a new agile team from staff you already have. Unfortunately, creating an integrated team with only the roles we already have is not going to solve either of our two problems.

Firstly, we don’t have an easy-to-understand mockup because it’s nobody’s job. If we smooshed everyone together at this point, you likely don’t have anyone familiar with the ideation process which leads to creating mockups or testable prototypes, as product design roles are not common in the federal government.

Secondly, on the lack of prioritization and product thinking, there is an even bigger gap here. Collectively, formalized enterprise processes are about creating more certainty as the project progresses. What starts out as a concept in a business case becomes modelled in different ways — as a technical system, as a list of features — essentially following a linear path where we continue to add detail without really validating that new additions are needed or even useful. (In Canada’s Guide to Project Gating, “user needs” are mentioned in the first three planning phases, but not in subsequent implementation phases.)

Creating a new, composite team that ‘works agile’ (ie, does sprints) doesn’t solve the problem that we are missing ways of gaining crucial insight about our product (eg, usability testing, user feedback, market research). Agile teams in departments are usually granted leeway to experiment with new approaches outside of conventional product gating, but without specifically staffing teams to prioritize gaining actionable feedback, your most likely outcome will be teams that fall back on existing linear processes out of habit, losing a critical benefit of agile workflows.

Recommendations

Don’t worry though, it’s still an article by Agile Paul and so ‘Agile Will Save You’ is right around the corner. I’m not saying agile is unworkable here, only that assembling new teams to experiment with new workflows without adding new skills creates gaps which we need to address. There are 2 issues to fix here: (1) What is the thing? and (2) What’s important about the thing? and, luckily, both of these map pretty cleanly onto job titles.

Specifically, we need to introduce 2 new roles:

- A Designer to get you to a place where you can create and test mockups.

- A Product Manager to prioritize what we’re building and why, not to just blindly lead the team to build whatever made it into our slide deck.

1. Hire a Designer

Designers are an essential part of any agile digital service team. Simplistically, a Designer is tasked with producing and iterating on mockups/wireframes — definitely a gap we have now — but this recommendation is broader than that.

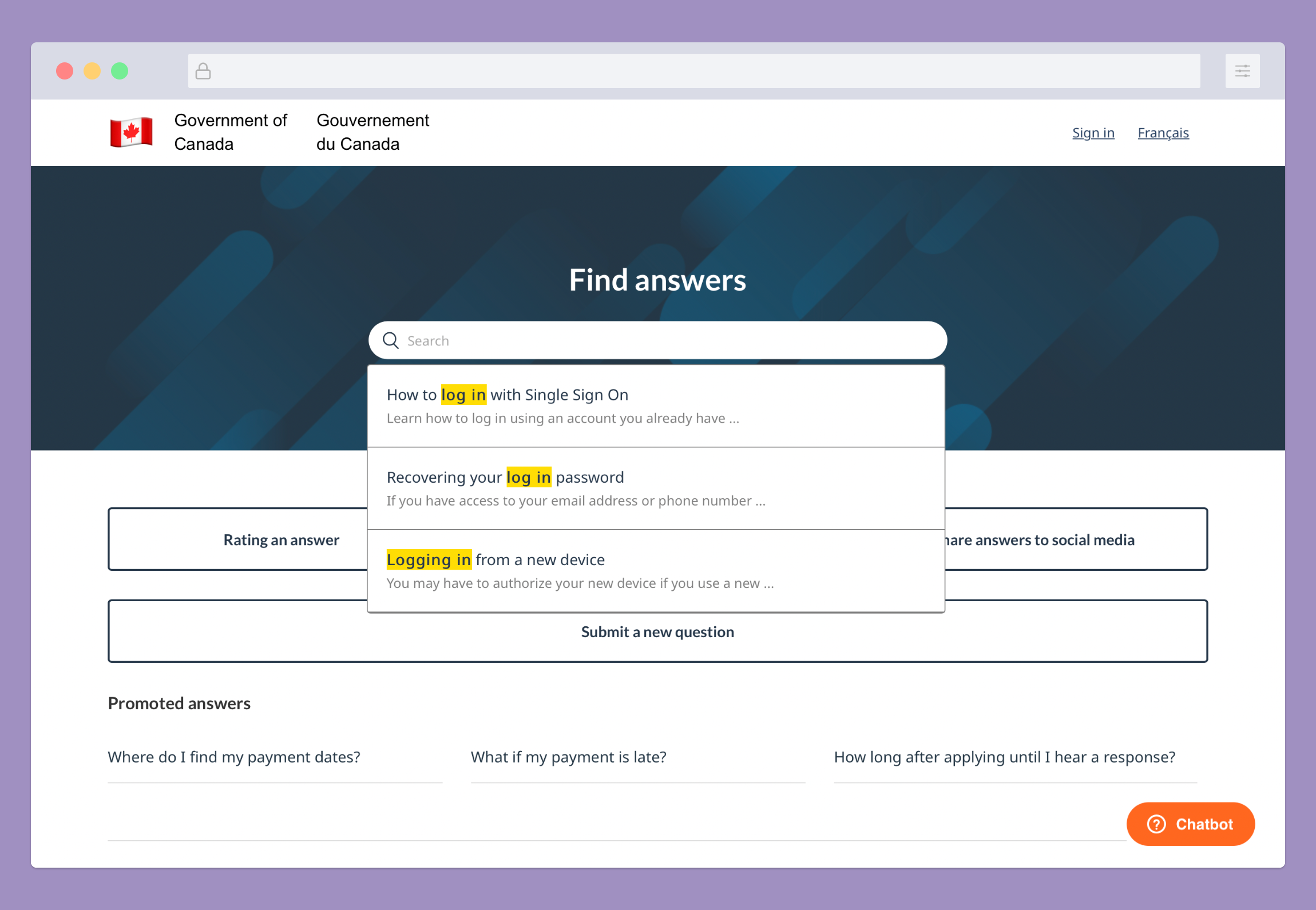

The core skill set of Designers is the ability to condense abstract problems into a defined solution that balances practicality with utility. I’ve focused on the mockup because it’s the most tangible artefact of our new Knowledge Base, but, more holistically, designers are responsible for the process of arriving at an initial concept with the team, and continually testing/validating it over time. A Designer will investigate the problem, understand the context (what other solutions exist, what do we have now, how do people get here?), determine who the end users are, and advocate on their behalf. In the end, Designers propose solutions in the shape of wireframes, mockups, or click-through prototypes. Here’s what a mockup of our Knowledge Base might look like:

Figure 5: Sample mockup of the Knowledge Base homepage

A sample mockup of the homepage of our hypothetical Knowledge Base.

So, we’re definitely headed in the right direction, but mockups are still just a ‘best guess’ about what we think is the best way forward. And like with any guess, you still might be wrong. It’s important to emphasize that a Designer’s role goes beyond just producing mockups or presentations, but includes actually validating that mockup with stakeholders and end users to increase our confidence as we move from a card castle of educated guesses to a concrete Actually Existing product.

That being said, the first step towards gathering usable feedback is arriving at a design that looks like what we’re trying to build (even if it’s just lo-fi prototyping). This is not possible with the other artefacts we have created thus far, but mockups are something that everyone can understand without being fluent in Unified Modelling Language.

2. Hire a Product Manager

The Product Manager (PM) is accountable for the overall success of a product — almost like a mini CEO. Product Managers know what is needed and why it is needed: using evidence from user feedback, product metrics, and external research to set a product vision and a roadmap to get there. An important distinction is that Product Management isn’t about executing a predetermined plan, but charting a course towards building the best practical solution based on available evidence.

If we go back to the slide deck example, we can see a laundry list of possible features with no explanation of how they might fit together. If we created a mockup of a product with all these features, we can at least imagine what the heck this might look like. But we are still talking about building The Homer Car: cramming everything you possibly could into a bloated and confusing product.

If you contract a vendor dev team to implement everything on your list and make payment contingent on that, you create a bunch of perverse incentives, and you also lose control of your scope and the quality of the outcome. There’s no real sense of what is important to users or what kind of compromises are tolerable — you’re locked in.

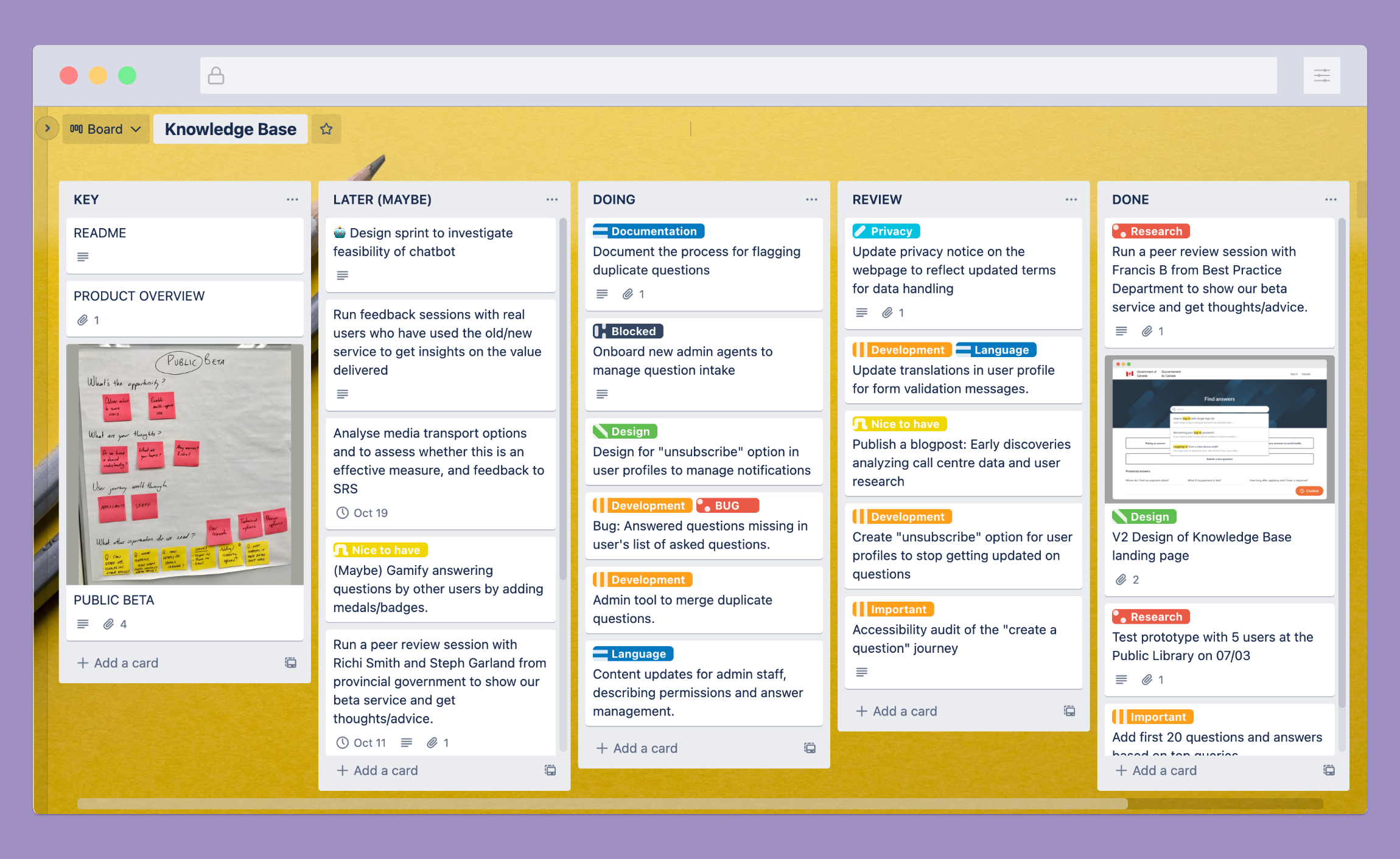

Your PM ultimately establishes your list of desired features and prioritizes them. Without explicit product ownership, you can end up with some pretty awkward products, with superfluous features crowbarred just because they were in a document somewhere. Product managers act as a funnel, listening to all the various groups, and condensing that information into something workable. A PM’s representation of the product is a backlog of all the ongoing work:

Figure 6: Sample backlog

A sample backlog for a hypothetical in-development Knowledge Base.

A good backlog is up-to-date and prioritized: all ongoing work is visible and 'for-later' items are kept track of. On the waterfall teams I’ve been a part of, everyone is obsessed with planning but on a day-to-day level there is very little clarity on what people are working on and what state things are in. It’s common that team members are moonlighting on many different tasks at once but without any real sense of progress or priority. In contrast, a well-ordered backlog is essential for making sure the team is always pulling in the same direction, supporting each other where possible, and highlighting blockers so that they can be resolved.

Potential barriers

So that’s it then, just hire two new staff members and away we go, eh? Well, not quite. In keeping with the everything-comes-in-twos theme, I’ll briefly outline two barriers you will likely run into.

The process barrier

Current gating processes emphasize an approvals-based “figure-it-all-out-before-doing-anything” workflow where teams are given a predetermined solution to execute on. There is some sense in this, given that single-discipline teams are the norm in large departments. Building any digital product is a multidisciplinary activity (requiring input from policy, design, development, security, architecture, etc), but enterprise orgs don’t typically allow for heterogenius team structures able to efficiently compile diverse input on a day-to-day basis. Instead, the ‘waterfall’ solution is to create an internal assembly line where these various groups add their particular weld or coat of paint to every product as it passes by — think of how cars are assembled on a factory floor: each station on the conveyor belt is responsible for one aspect of every car. In this traditional approach, interactions between disciplines are defined upfront by an org-wide linear process.

In contrast, multi-disciplinary agile teams bring these varied disciplines into close collaboration, prioritizing quick feedback and iterative changes. This fundamental change in approach requires strong facilitation skills: losing the structure of a waterfall process means the team is responsible for defining its own workflow, something existing staff are not likely to have seen before. This is where a Designer and Product Manager are essential: Designers lead the product design by facilitating team collaboration, while Product Managers plan an overall team strategy, prioritize upcoming tasks, and delegate responsibilities.

However, just as abandoning your waterfall process without hiring new roles probably won’t work, hiring new roles without changing your waterfall process is a similarly bad idea. If you already have a signed-off requirements list for a Designer to mock up and a fixed timeline for a Product Manager to have everything done by, you are setting them up to fail. Bringing in Designers and/or Product Managers is the right idea, but they need the right conditions to succeed. Without creating space for working through unknowns, collecting feedback, and iterating as you go, you risk a scenario where you hire great people only for them to hit a wall as they run up against legacy processes fundamentally at odds with their skillset.

The hiring barrier

‘But I can’t hire Designers or Product Managers in my department!’

I’m glad you brought it up. For anyone still reading (hello, huge kudos!) one of the biggest obstacles to taking this advice is related to hiring in the Canadian government. I’m not an HR professional, so I’m not an expert on hiring in government, but to be brief, the Canadian government is a unionized workforce and when you’re hiring people in, you have to match them to an already-existing job classification. As a Developer, I am part of the ‘IT’ group (previously the ‘CS’ group), if you are an Economist, you are part of the ‘EC’ group. But there is not yet any set classification for Designers or Product Managers. What this means is that you have to do what you can. Sometimes you can pilot bringing in new roles under a generic classification, sometimes you have the go-ahead to hire contractors, or you might know colleagues keen to take on the role themselves.

Again, I am not an HR or policy specialist so I understand this is a problem, but specific solutions will depend on your context. If you know other PMs or Designers in government, ask them how they got the job, or join the Slack group for GC Designers and see if anyone can give you advice.

But, even though it might be hard to get some of these new roles in, you really should spend whatever political capital you have here. Every agile ‘pathfinder’ project that fails serves to discredit similar initiatives in the future (and vice-versa), so it’s important to put together the strongest team you can.

Modern roles for modern teams

So there you go, two cut-and-dry recommendations for you: get yourself a Designer and a Product Manager. Since these two roles are not yet formalized in official federal job classifications, they are likely to be missed in most small-scale innovation projects. So it may not be easy to find them, but, then again, it might not be as hard as you think! While there aren’t too many many Designers or PMs in federal government (yet!), those that are often find themselves siloed on innovation projects that are more demonstrative than practical. If you have a shot at building an Actual Product that’s going to be released, that’s an opportunity you can offer someone who feels like they’re not getting that same chance with their current team.

For the time being, ‘Innovation’ projects (or ‘pathfinder’ projects) in government will always be some compromise between a ‘pure’ agile workflow and the rules-based waterfall processes the department is comfortable with, but they are still your best bet for effecting change inside of risk-averse departments. In order to create better conditions for yourself, it helps a lot to have a success or two under your belt, and you will only get those if you take advantage of opportunities where you can find them. Whenever you find yourself on one of these teams, you’ll want to stack the deck in your favour as much as possible, and that means: Move Fast and Be Safe while you focus on Building One Thing That Works with your two new friends, your Designer and Product Manager.